This issue offers an exploration of art production in contemporary Shanghai through the lens of the persistently evasive concept of modernity. Shanghai was hailed as China's “gateway,” “engine room” and “icon” of modernity. The Japanese invasion and the rise to power of the Communist Party, characterized by a cultural vision rooted in rural peasantry, reduced cosmopolitan Shanghai of the 1920s and '30s to the state of an inert “sleeping beauty.” In the wake of late-twentieth-century China's “reform and opening up,” Shanghai was restructured as an outpost for China's development, and consequently became a specter of a previous era. As Nick Land wrote in the pamphlet “A Time-Traveler's Guide to Shanghai,” the city “reverted to the present from a discarded future, whilst excavating an unused future from the past.” The modernity of today's Shanghai, “modernity 2.0”—or what Land calls neo-modernity—translates into an urban landscape that questions the very notion of temporal linearity. In her book

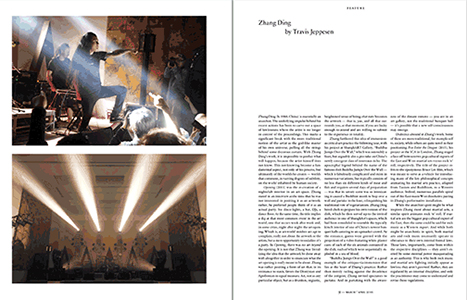

Shanghai Future, Anna Greenspan wrote: “In [Shanghai's] bars, cafes, teahouses, parks and boutiques, urban inhabitants play out their roles in [a] time-travel fantasy. Through its architecture, design, self-image and style, contemporary Shanghai strives to remember, and to reinvent, the creative flourishing it once—too briefly—hosted. Driven by this fractured destiny, it is embedded in a spiral of time, actively trying to splice together its imminent future with a past futurism that never had the chance to play itself out.” Art production in Shanghai today triggers a similar “time spiral” via an ongoing debate concerning tradition and the achievement of modernity as expressed by “new” avant-garde languages. Six profiles of Shanghai-based artists and collectives—Zhang Ding, Jin Shan, Li Qing, Grass Stage, Tang Dixin and Yu Ji, by

Travis Jeppesen, Azure Wu, Michele D'Aurizio, Rebecca Catching, Xin Wang and Jo-ey Tang, respectively—attempt to better understand this local debate. Additionally, three roundtables with artists, critics and thinkers ,

Yang Fudong and Xu Zhen consider how a coexisting “old” and “neo-modern” Shanghai is reflected in the city's art scene. Visual projects by

Birdhead and Lu Pingyuan phase the contents' sequence. Finally, this issue introduces two new columns: “Data” and “Macro.” The first is intended as a graphic exploration of art-industry phenomena, in this case a timeline of Shanghai's “museum boom” of the last decade, compiled by Hanlu Zhang. In “Macro”—a theoretical essay that will delve into each issue's general problematic—Greenspan and Land develop the concept of neo-modernity through their study of the traditional genre of calligraphic abstraction