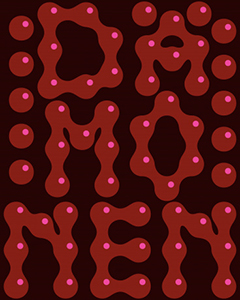

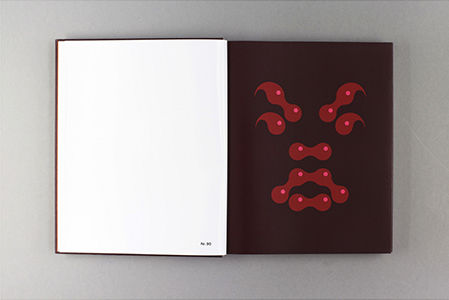

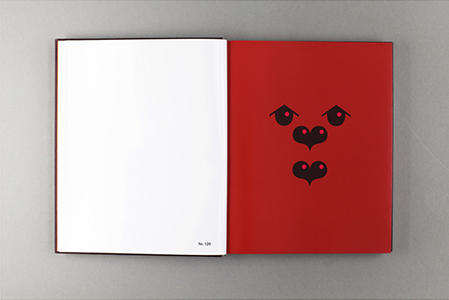

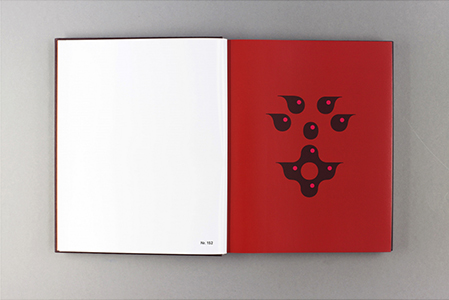

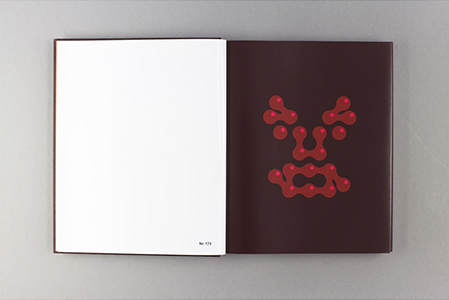

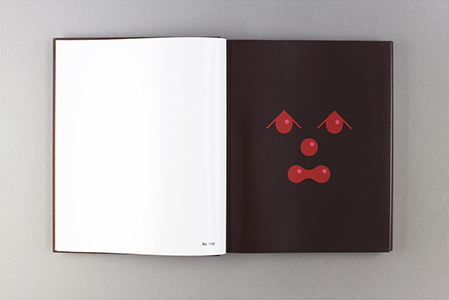

What would a current-day demon look like? The Swiss artist playfully rehabilitates these evil figures in 170 minimalist portraits—rendering them as an ideal type of the postmodern, at once terrifying and comical.

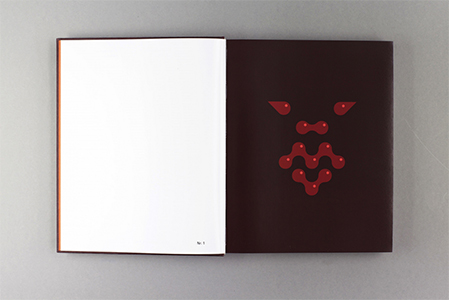

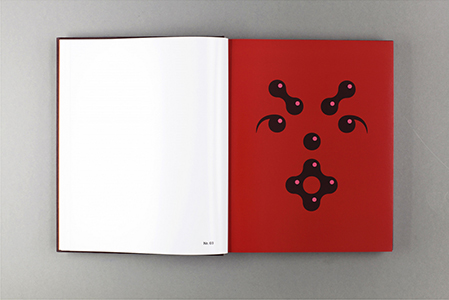

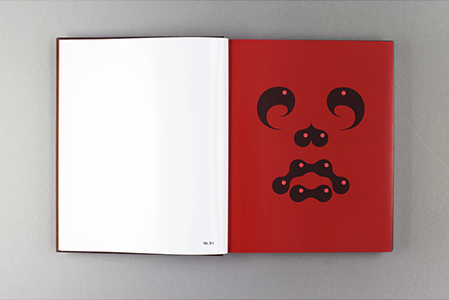

Demons are mutable, their existence dependent on context. So, too, this series of 170-odd pictures by Swiss artist Anton Bruhin, is wholly dependent on what the eye sees in them. They appeal to the imagination, the pre-existing mental images in which we range our visual impressions. They play on patterns and archetypes innate to the human mind. Bruhin's demons betray a profound sense of the nature of suggestion.

But what would a current-day demon look like? The free-floating ghosts of yore, personifying vital and cosmic energies, were displaced over the centuries from the outside world into the inner life of living creatures, especially human beings, and came to be associated with evil: malevolent spirits that slip into things to whip them into a frenzy, to foist maladies and iniquities upon them, to unhinge them and set the destructive powers of fate on them.

Bruhin seems hell-bent on playfully rehabilitating the demon by portraying it as an ideal type of the postmodern, at once terrifying and comical. That it should assume the recognizable form of a face is hardly surprising. Bruhin's pictorial experiments here, abstractly composed as they may be, invariably culminate in an amusing clarity. His pixelated creatures look hard-drinking, capable of irony, often jovial and delighting in flaunting their peculiarities. The longer you bounce back and forth between them, the more wondrously their facial expressions seem to epitomize states between gentle otherworldliness, an urge to smirk and a spooky furiousness: globular eyeballs of grease winking up at us from out of the primeval soup. Some are misshapen, some have weird feet. They may be grinning or belching, besprinkled with strange shades of yellow slime or with warts. But they merely toy with the terror they're supposed to personify, laughing about it even as they spread it. They seem to know the viewer is their confederate in mischievousness.

(Michel Mettler)

In the 1960s, Anton Bruhin (born 1949) first began organizing happenings and performances, designing and typesetting his own books, which he self-published with Hannes R. Bossert through April-Verlag, drawing, and writing prose and poetry. It was mainly his drawings and poetry that attracted notice in the '70s. As an exponent of the nascent bohemian and contemporary art scene at the time, his works were included in epoch-making exhibitions, such as “Mentalität” “Zeichnung” (Kunstmuseum Luzern, 1976), “Saus und Braus” (Strauhof Zurich, 1980) and “Bilder” (Kunstmuseum Winterthur, 1981). In the 1980s, Bruhin turned primarily to painting landscapes and townscapes

en plein air, whilst also painting interiors and portraits of friends and acquaintances. And in the '90s, he focused mainly on music and poetry, composing palindromes and other forms of experimental lyric poetry, and devoting himself extensively and intensively to one of the oldest instruments in the world, the Jew's harp (aka

scacciapensieri in Italian,

Maultrommel or

Brummeisen in German,

Trümpi in Swiss German). After the turn of the millennium he returned to pictorial art, painting, drawing, working on digital pictorial worlds and his DIY publishing strategy. Every year Bruhin puts together a new little artist's book and prints and sends out a small quantity to his personal circle.

After an apprenticeship in typesetting, Anton Bruhin was a member of the first class to study at the F+F School with Serge Stauffer, famous art teacher and specialist in

Marcel Duchamp, where he came into contact with

concrete poetry,

Fluxus and

experimental music. These genres have interested him ever since, inspiring him to produce vinyl records (e.g.

Vom Goldabfischen, 1970, and

rotomotor, 1978), experimental poetry (e.g.

Reihe Hier) and palindromes (1991-2002

Spiegelgedichte).

Dieter Roth and André Thomkins are recognizable influences, as are Philippe Schibig and Friedrich Kuhn—a generation of artists on the cusp of the transition from late modern to “contemporary art”, who in recent years have increasingly been the focus of an art historical re-examination. Like Bruhin, they combine themes of excess and chaos with a pragmatic interest in graphic solutions and simple structural schemas. He clearly enjoys serial approaches, taking pleasure in setting his own parameters and producing visual grammars, which are sounded out, extended and expanded to explore their every possibility and permutation. Having tested such an array, he then builds another system in which to seek all the statements that can possibly be constructed w ithin those parameters.

Bruhin exemplifies a generation of

Swiss artists who build on the recent past, always playfully subverting it, too, and liberating it from existential pathos, as in the early works of

David Weiss or Markus Raetz, with whom he resided in the Swiss artists' village of Carona. The upshot of a sea change in Swiss art, Bruhin's work was itself an impetus for Swiss contemporary art as it first took form in the late '60s with artists like Urs Lüthi,

Manon and Jean-Frederic Schnyder in close connection with the alternative and hippie subculture movements of the period.