“Crimes against humanity,” especially genocide, have been excluded from amnesty since the Nuremburg Trials. On a cultural level, oblivion by decree becomes an obligation to remember. This reversal is well-intended, but it opens up critical questions: Can memory be permanently established? Is it possible to maintain it in a monument?

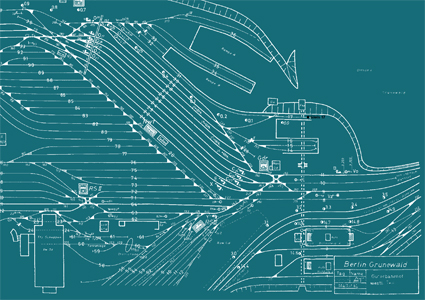

The intervention at Track 17 at Berlin-Grunewald station, a work by architects

Nikolaus Hirsch, Wolfgang Lorch, and Andrea Wandel on the site of the deportations from Berlin between 1941 and 1945, is an attempt that aims at a structural connection between memory and oblivion. Referring to Alois Riegl's (the founder of the “Modern Cult of Monuments”) differentiation between the specific, highly controlled documentary value, and the generic, always changing “age value,” the authors introduce a strategy that negotiates between stable and instable parameters: presumably permanent data, shifting vegetal successions, material durations and decay. This approach investigates whether it is possible to build ambivalence or even doubt into a monument. Thus, the uncertain status of the material memory becomes the focus of the intervention at Track 17.

The editors' work includes the Dresden Synagogue, the Hinzert Document Center, a high-rise building in the geopolitical hotspot of Tbilisi (Georgia), and the highly debated Archeological Zone / Jewish Museum in Cologne.

"If the efforts of a Holocaust-centered culture of memory could have any

effect, it would be to make understandable that, under certain circumstances,

it is not only bad people who behave inhumanly, but good ones, too. That is

the problem. Track 17 is neither located on the site of a former concentration

camp, nor in an industrial zone. Instead, it is found in the middle of one of

the most bourgeois, most saturated quarters of the capital."

Harald Welzer

Photos by Gerald Domenig and Lukas Roth.