The first survey of Troy Brauntuch's work, including newly commissioned essays by Johanna Burton and Douglas Eklund (the curator of the recent "

Pictures Generation" exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York).

A member of the so-called "

Pictures Generation," Troy Brauntuch (*1954)âwhose career spans some three decadesâhas often been characterized, with his peer

Jack Goldstein, as taking a postmodern attitude toward representation. He is well known for his works from the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s in which he decontextualized what would otherwise be hyperbolically charged content. For example, as Johanna Burton puts it, "a 1977 series of photographic screenprints with the simple title "1 2 3" was made using borrowed imagery: unremarkable sketches of a tank, a vestibule, and a stage set. There is no accompanying caption or other text with which to site these fragmentary clues, whose immediate capacity to signify has been temporarily tampered with. The appropriated sketches were, it turns out, penned by Adolf Hitler, whose name, of course, once divulged, imparts overwhelming significance to otherwise rather insignificant images."

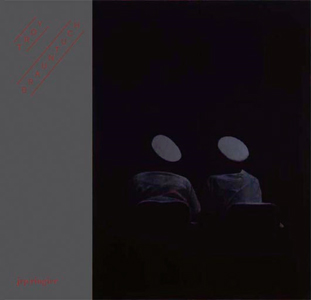

In his most recent work, Brauntuch extends his investigations to the space between a thing and our idea of it. If he is still leaning on the photographic even while utilizing a variety of media, in his contÃĐ crayon works on black cotton, explains Burton, "the images feel as though they were conjured from the deep recesses of phantasmic space. What appear at first to be monochromatic canvases reveal photo-derived images (a woman's polka-dotted coat, the supine form of a cat) that coagulate and rise to the surface, barely there. In his photographs, everyday objects assert their ephemerality, and a tangible, intimate silence seems as much a part of the pictures as the simple domestic scenes they convey."